Warning: spoilers abound ahead.

If you are looking for a book to pack for vacation this summer, I’m putting my suggestion in for Margaret Kennedy’s riveting 1949 novel, The Feast, a darkly entertaining story about the death of seven people on holiday in the fictional Pendizack Cove, Cornwall.

In the prologue we learn that an overhanging cliff has crushed a seaside hotel and that there are both victims and survivors. The narrative then immediately turns back to the start of the week preceding the disaster. It’s through often seemingly inconsequential details, such as gossip between maids or children’s games, that we get to know the victims and the survivors and learn what it is that will set them fatally apart.

The idea for the novel came to Kennedy in the 1930s during a discussion with fellow writers in which they challenged one another to write a modern day version of a medieval allegory of the seven deadly sins. So the book can be read as a kind of puzzle inviting the reader to try to work out which character symbolizes which sin and thus will end up dead.

Kennedy’s engrossing writing and the clever puzzle aspect of the book would be enough to recommend the novel. But what makes the work richer than a simple allegory is not so much the seven vicious characters on their own but a reflection on morality that emerges from the context of their relationships with other characters.

Each of the seven sinful persons is closely linked to one or more other characters—a spouse, children, or employees—who are striving to various degrees for virtue in the face of intense external and internal pressures. It's through the depiction of these fraught relationships that the novel explores under what conditions vice festers and destroys the human soul and virtue develops and ennobles it.

Quite ingeniously, each of these foil characters embody precisely the virtue that is considered remedial to the vice of the character with whom they are connected.

For instance, patience is the virtue that is traditionally contrary to the vice of wrath. The wrathful Canon Wraxton’s adult daughter and helper, Evangeline, is an oppressed, anxious, and undeveloped person at the start of the novel. She believes that patience means she must conform her life to the duty of enduring and managing her father’s volatile tempers. By the end, she is free from him and has become a person “fully alive”. She no longer enables her father’s tyranny through a malformed conception of patience, but now possesses a true understanding of that virtue. She waits and works alongside the man she loves as they patiently look forward to a bright future in marriage.

Just as Canon Wraxton’s wrath has stunted his daughter’s spiritual growth, Mrs. Cove’s covetousness has twisted her three daughters’ understanding of friendship into something they view as transactional. When she is offered candy on the train to Pendizack, Blanche tries to refuse because she has nothing to offer in return. But by the end of the novel, Blanche and her sisters understand that generosity, the antidote to greed, is meant to be given and accepted freely. The Cove children give the titular feast, inviting everyone to a seaside picnic, which is, at the same time, a vision of the grace-filled heavenly banquet.

What works this change in the characters who grow in virtue and ultimately survive? Chiefly friendship. At the start of the novel, the hotel proprietor’s husband jests that his sons wished to call the house Hell’s Hotel after an old name for the area. But this turns out to be no joke as all the characters come to Pendizack Manor Hotel locked in the little hells of their isolated, unhealthy relationships.

The characters who long to be free, both free from the external oppression of their vicious companions and free in an interior, spiritual sense, come into contact with one another. They console and encourage each other. They open each other’s eyes to the idea that life can be a banquet, heaven experienced on earth, if one is in true communion with others. Near the end of the novel, it is said of the couple, Evangeline Wraxton and Gerry Siddal, that “happiness had transformed them.”1 The same can be said of all the virtuous characters. If Pendizack Manor Hotel is identified as hell at the outset of the story, the rest of the narrative is a Dante-esque movement upward to paradise for the characters striving in virtue.

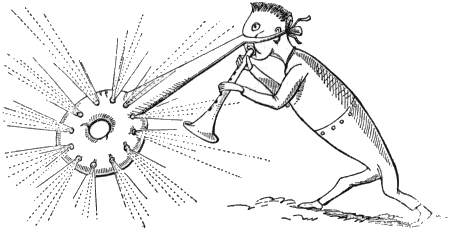

And how is it that virtue becomes the literal saving grace for these characters? The clue lies in the title. The feast that the Cove children want to give is an act of gratitude to the characters who have befriended them and raised their sights to something higher and more radiant than the constricted life they’ve only ever known. They plan a nighttime picnic at the top of the cliffs and in gratuitous generosity, invite everyone, even the vicious characters. Delightfully and significantly, the children make it a costume party taking it’s theme from Edward Lear’s nonsense verses.

Some characters, like Evangeline, enter into the fun whole-heartedly, making costumes and food, helping the children design invitations, and encouraging the other adults to attend.

Other characters just barely make it up the cliffside for the feast. Unlike Evangeline, whose capacity for friendship, virtue, and grace is greater, these characters, such as Mrs. Siddal and her son Jock, are slower to respond to the grace that other characters extend to them and slower, too, in their growth in virtue.

Mrs. Siddal, the hotel’s proprietor and a woman weighed down by her husband, the living embodiment of sloth, has no plans to join the feast when she sees that the revelers have forgotten the wine. In an act of diligence, the counterpoint to sloth, she decides to carry the wine up to the feast. The scene that follows echoes Dante’s Purgatorio with Mrs. Siddal struggling with her heavy load up the cliffside. Just as Dante has his penitents encourage and help each other as they ascend Mount Purgatory, Kennedy has Jock help his mother with the wine and has young Beatrice Cove descend to share her excitement and spur them onwards and upwards.

It is the seven sinful characters who, by declining their invitations, make the fatal choice to stay at the hotel where they will be crushed by the landslide. They feel they are too grown-up and sensible to participate in childish antics. However, these characters who put such stock in their own good sense are the ones who are intellectually and spiritually untethered from reality.

Mr. Paley, the prideful man, believes he is the author of his own existence: “I do not think that I owe anything to anybody. What I am, what I have, are the result of my own efforts.”2 Mrs. Cove is consumed with an imaginary future only possible if her daughters die and she receives the money allocated for them. The envious Ms. Ellis suspects everyone has an easier life than she does and consequently bears ill-will to all.

Milton famously said in Paradise Lost: “The mind is its own place, and in itself can make a heaven of hell, a hell of heaven.” It is fitting that Mr. Paley inwardly cries out: “‘Why this is Hell! Nor am I out of it. But that line, that line, haunts me wherever I am. I can never escape from it.’”3 Throughout the course of the novel, the seven vicious characters have repeatedly shut themselves off from others, suffered in self-inflicted isolation, and complained about the unfairness of their circumstances.

It is illuminating to find that on the topic of intellectual sight, St. Thomas Aquinas wrote that intellectual blindness “is a punishment, in so far as the privation of the light of grace is a punishment. Hence it is written concerning some (Wisdom 2:21): ‘Their own malice blinded them.’”4

It is the children and adults scorned for being unrealistic who are truly grounded in reality. They are ultimately the ones who stand on firm ground high above the ruins of the hotel. They are the ones who see by the light of grace. The characters who have persisted in spiritual blindness are literally blinded and crushed by the earth in the end.

The seven vicious characters refuse to come to the feast. They refuse “change and become like children”, and so they do “not enter the kingdom of heaven” (Matthew 18:3). Instead, they become the victims they have always believed themselves to be.

If I’ve made The Feast sound like a heavy read weighed down by plodding intellectualism, fear not! It wears its allegory lightly and by the midway point, I was tearing through the pages. It's a thrilling and very funny book. You should absolutely take it on your summer vacation, of course, that is as long as you are pure of heart and not headed somewhere with cliffs of questionable structural integrity.

I recommend it especially for fans of: The Bridge of San Luis Rey, The Fortnight in September, Agatha Christie, or Dorothy Whipple.

Margaret Kennedy, The Feast, (New York: Mcnally Editions, 2023), 250.

Ibid., 267

Ibid., 16

Aquinas, Summa Theologica, II-II, Q. 15, Art. 1

Brava Dominika! I enjoyed reading this so much. You brought out new texture and depth in the story for me, such as how the characters who survive exhibit corresponding virtues. Your exploration of Dante is also so great with the characters who survive going up Mt Purgatory to reach the heavenly feast. That’s just so great! I didn’t grow up in my Presbyterian tradition with learning about virtue and vice and your understanding of it here within the context of the novel makes me long to learn more.

Love reading your thoughts Dominika!! After Dante, May have to read this one ❤️!