Kazuo Ishiguro's "Never Let Me Go" and the Theology of the Body

“We will only be able to understand ourselves when we understand the universe. Our present is filled with the past.” -Charles de Koninck

Two things before we begin: (1) This post is full of spoilers. However, I was aware of the big ‘twist’ in the novel prior to reading it and it didn’t diminish my experience. Read at your discretion. (2) I am a Bookshop affiliate. If you make a purchase through my link, I will earn a commission which helps me continue to recommend books and write reflections like this one for readers of Gathering Light.

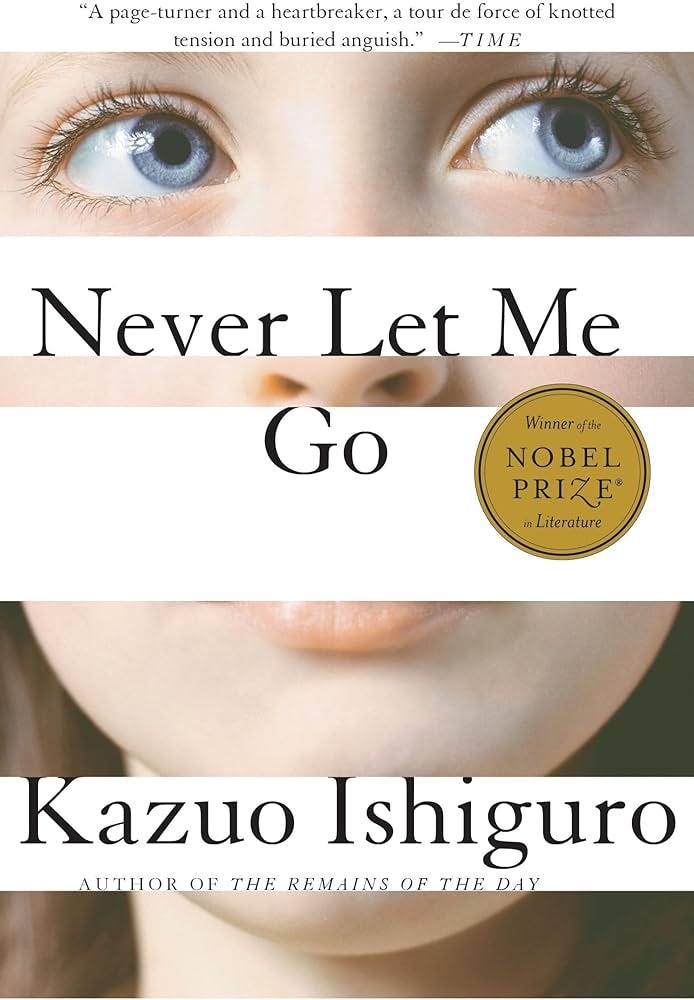

I’ve written before of the particularly modern condition of spiritual orphanhood1—that a secular, materialist worldview cuts us off from both our origin and destiny and results in a people who are adrift in the world. Few works of literature render the ill effects of this severing from identity more poignantly than Kazuo Ishiguro’s 2005 novel, Never Let Me Go.

From the start we know there’s something off about the children who attend the idyllic private school Hailsham. Our narrator, a former pupil, Kathy, reflects back on the formative years she spent there, and her memories slowly reveal the awful reality that she and her peers are clones created for the purpose of donating their vital organs. The novel explores Kathy’s relationships with her Hailsham classmates, Tommy and Ruth, as they make their way to adulthood to become carers for other organ donors and eventually donors themselves.

Never Let Me Go is sometimes characterized as a sci-fi or dystopian work, but it’s less concerned with the technological aspect of cloning, instead taking a philosophical and psychological approach towards these children’s condition. Ishiguro considers what it would do to a person’s psyche to know he or she has been created to be discarded.

I happened to be teaching a “Philosophy of the Human Person” course for high school freshman at the same time that I was first reading Never Let Me Go. In this class informed by Aristotelian and Thomistic philosophy, we considered such questions as: what is the nature of the human soul, what sets us apart from plants and animals, what is the origin and destiny of man, and of what does human happiness consist.2

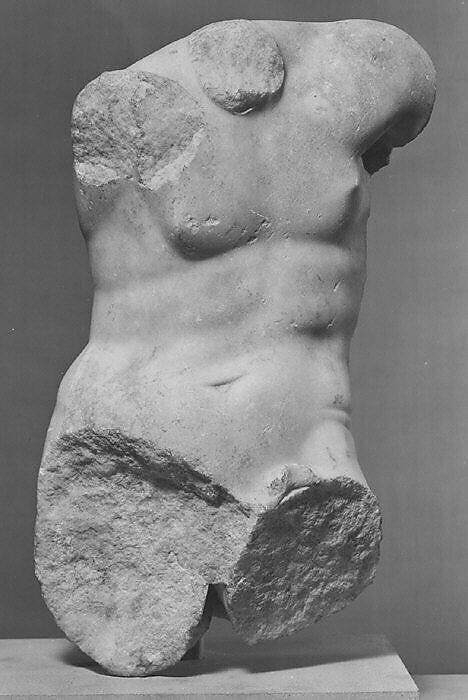

I’m simplifying here but the main gist for the students to take away was that the human person is a body-soul composite (an embodied soul or ensouled body but never a ‘soul within a body’) possessing inherent dignity, that we are made for happiness, and that happiness is found in love, or communion, with others and ultimately with God.

The second half of the semester we used Pope John Paul II’s teachings in his Theology of the Body to discuss what it means, practically speaking, that the human person is made for love. It was serendipitous to find, as I listened to the audiobook of Never Let Me Go on my commute that semester, that the pope’s writings uniquely illumined Ishiguro’s characters and brought the stakes of their lives into greater focus.

Such a radiant expression of the human person—made by love and for love—is a far cry from the idea that a person is merely material made to be destroyed. Kathy and her friends’ lives make explicit the tragedy that follows when we’ve lost our ability to articulate the real definition and destiny of the human person.

In the Theology of the Body, John Paul II names three original experiences of man, experienced first by Adam and Eve in the text of Genesis but also, in a less overt but still foundational way, by all of us. And because Ishiguro creates such deeply human characters, you can see the traces of the three original experiences in them too.

The first of these experiences is original solitude. In the garden, Adam is aware of himself as being apart and distinct from all other creatures:

From the first moment of his existence, created man finds himself before God as if in search of his own entity. It could be said he is in search of the definition of himself…[His self-consciousness] brings him out of his own being, man at the same time reveals himself to himself in all the peculiarity of his being.3

Kathy and her peers are also in search of the definition of themselves. They have no parents from whom they receive their identity. Despite their school guardians’ attempts to give them an enriching education and a sense of dignity, they lack the language of a robust philosophical anthropology. Kathy doesn't know who she is or what she is for outside of the utilitarian purpose of donating her organs.

Still, the question of where they've come from, this original solitude, haunts Kathy and her friends and shows up, in particular, in their conversations surrounding their “possibles”, the people from whom they’ve been copied. It’s an unsettling topic for the Kathy and her peers but one with which they are “fascinated” and “obsessed”, because, as Kathy explains:

We all of us, to varying degrees, believed that when you saw the person you were copied from, you'd get some insight into who you were deep down, and maybe too, you'd see something of what your life held in store.

They want to see themselves in the context of a full, flourishing life—one that’s not been bred in isolation to be exploited. They want to hope that their lives mean something more than their eventual ends seems to suggest.

At one point, the friends take a trip to get a glimpse of a woman who might be Ruth’s possible. The endeavor is unsuccessful, and in a tirade of rage and anguish, Ruth expresses what she and her peers really believe of themselves:

We all know it. We're modelled from trash. Junkies, prostitutes, winos, tramps. Convicts, maybe, just so long as they aren't psychos. That's what we come from…If you want to look for possibles, if you want to do it properly, then you look in the gutter. You look in rubbish bins. Look down the toilet, that's where you'll find where we all came from.

Kathy, herself, secretly looks through porn magazines to find her possible. And when Tommy catches her at it, he says, “You weren't doing it for kicks. I could tell…It's your face, Kath…you had a strange face. Like you were sad, maybe. And a bit scared.”

I don't wholly resonate with Rachel Cusk’s reading of Never Let Me Go, but I find this claim she makes about Ishiguro's vision insightful: “what he concludes is that a child without parents has no defence against death; that its body is not sacred, that it is a force of pure mortality. The parent is a kind of god, sanctifying and redeeming the child."

That security in the knowledge of one's origin, (at the very least one’s natural origins and, so much the better, one’s spiritual origin), can do much to buffet a person from the inevitable suffering and uncertainty in this life and to imbue the body, born and received into a particular family, with meaning and ‘sacredness’.

But the cloned children are, in the words of poet Franz Wright, “death row born and bred”. They do not know what it means to be fashioned out of love.

Original unity, the second of the original experiences in the Theology of the Body, refers to the greater self-understanding Adam receives by beholding Eve. He sees that she is like him: “this at last is bone of my bones and flesh of my flesh”.

Original unity expresses the truth that we learn who we are through interpersonal relationship. On the topic of original unity, theologian Rachel M. Coleman notes that, “the image of a mother and a child is also very apt here: the child learns, through his mother’s embrace and her smile, who he is.” And this underscores Cusk’s comment that Ishiguro believes the parent-child relationship is essential for a secure identity.

But in experiencing original unity, Adam not only recognizes another human person. He beholds an other to himself. He beholds a woman. He recognizes the distinction of his maleness and Eve’s femaleness. John Paul II writes that “the human body bears within it the signs of sex and is male or female by its nature” and these signs call for the “‘incarnate’ communion of persons”. Quite literally, the maleness and femaleness of our bodies communicate that humankind is designed for community. This is true in the very bodily sense of the generation of new life and the creation of the family, but also in the spiritual, non-sexual sense that we are meant for interpersonal relationships, such as friendship, which reflect and find their final fulfilment in the triune life of our creator.

Ishiguro’s clones are infertile by design. The purpose of the signs of sex their bodies bear has become unclear through technological manipulation. And their thwarted design results in their confusion surrounding the purpose of sexuality.

Their guardians attempt to give them guidance on the topic of sex, but this forced sterility, the intentional separating of the body from fertility, also confounds them as to the real purpose of sexuality. Kathy recalls:

Out there sex meant all sorts of things…And the reason it meant so much—so much more than, say, dancing or table-tennis—was because the people out there were different from us students: they could have babies from sex. That was why it was so important to them, this question of who did it with whom. And even though, as we knew, it was completely impossible for any of us to have babies, out there, we had to behave like them. We had to respect the rules and treat sex as something pretty special.

Their guardians know, on some level, that sex has meaning and ought not to be treated casually, but they don’t fully understand why. Kathy and her classmates have difficulty reconciling their guardians’ messages to “not be ashamed of [their] bodies” and “how sex [is] ‘a very beautiful gift’” with the reality of their embarrassed discouragement of the students actually engaging in sexual activity.

When the students go on to live in the Cottages, a transitional living arrangement between their schooling at Hailsham and training as carers, they have lots of casual, meaningless sex. They are unprepared for what is meant to be an act of fruitful mutual self-gift, and the disappointment of the experience comes through in Kathy’s reflections: “The atmosphere, like I say, was much more grown up. But when I look back, the sex at the Cottages seems a bit functional” and “even though we couldn't have babies from doing it, the sex had done funny things to my feelings.”

The last of the three foundational human experiences John Paul II describes is original nakedness which names Adam and Eve’s experience of being naked and unashamed. Coleman helpfully distinguishes between the three original experiences by linking original solitude to identity, original unity to community, and original nakedness to intimacy.

We are made to know and be known. Ishiguro’s characters implicitly know this truth. There is a rumor among them that if a couple really love one another, they can potentially get a deferral on their donations. It speaks to their tacit embodied knowledge of original nakedness that they believe their ability to love and be loved could overrule the utilitarian demand for their bodies.

The kind of intimacy that John Paul II describes in his teaching on original nakedness does not only refer to physical intimacy, but rather points beyond to man’s universal need to know and be known by his creator, who in turn desires to know and makes himself known to his creation. But Kathy is operating in a materialist framework which denies the very existence of her soul. And so, the search for identity that original solitude impels her towards never leads to her creator. The signs of her body that bespeak her natural fulfilment in community are muted. And the condition of original nakedness that exists deeply and unconsciously within her being never leads to an experience of intimacy that is free from anxiety. Her ability to know and be known is limited and clouded by the disordered telos imposed upon her.

Late in the novel, Kathy and Tommy begin a romance together and they hope their love might be deemed real and worthy of granting them more time. However, their relationship is “tinged with sadness” and they “hardly [discuss] anything openly”. They know, regardless if they are granted a deferral or not, that they must let go of one another in the end and that death has the final word. Tommy describes their situation with the following heartbreaking metaphor:

I keep thinking about this river somewhere, with the water moving really fast. And these two people in the water, trying to hold onto each other, holding on as hard as they can, but in the end it's just too much. The current's too strong. They've got to let go, drift apart. That's how I think it is with us. It's a shame, Kath, because we've loved each other all our lives. But in the end, we can't stay together forever.

When they are still children, Kathy’s teacher, Ms. Emily, gives a geography lesson in which she refers to Norfolk as England’s ‘lost corner’. The students subsequently develop a theory that Norfolk is “where all the lost property found in the country end[s] up”. Kathy says they were comforted by this idea, because when they’d lost something precious, they could one day find it again in Norfolk.

At the conclusion of the novel, Tommy has ‘completed’, the euphemism for having died following his organ donations. Kathy is still working as a carer and on one of her trips, she ends up stopping by a field in Norfolk where she notices trash along a fence.

I was thinking about the rubbish, the flapping plastic in the branches, the shore-line of odd stuff caught along the fencing, and I half-closed my eyes and imagined this was the spot where everything I'd ever lost since my childhood had washed up, and I was now standing here in front of it, and if I waited long enough, a tiny figure would appear on the horizon across the field, and gradually get larger until I'd see it was Tommy, and he'd wave, maybe even call. The fantasy never got beyond that—I didn't let it—and though the tears rolled down my face, I wasn't sobbing or out of my control. I just waited a bit, then turned back to the car, to drive off to wherever it was I was supposed to be.

Ishiguro’s novel is entangled with modern bioethical questions, because of course, without an adequate definition of the human person, what we may rightly do with the body through medical technology becomes precarious territory. But at its heart, Never Let Me Go is concerned with a much more fundamental question of human existence. It’s a question Franz Wright poses in his long poem, “Notes from the Cell”:

Is it your opinion that the world, beneath its tumultuous and often incomprehensible surface, is a vale in which souls are individually, painstakingly crafted one by one, as generally been held for some centuries, or do you find yourself siding with the radical but increasingly popular view of it as their slippery, gory, and unspeakable slaughterhouse?

It’s the same question Ishiguro wrestles with through the lives of Kathy, Tommy, and Ruth. The image we are left with at the end of the novel with Kathy juxtaposing all the precious, lost things of her life with the trash stuck in the ‘lost corner’ of England seems to suggest the second, hopeless view that Wright puts forth.

Yet John Paul II says that “man's experience of his body…seems to rest at such an ontological depth that man does not perceive it in his own everyday life.” All of us are blinded by sin, wounded by the failings of our own wounded parents, and quite simply, in the words of T.S. Eliot, “distracted by distraction from distraction”. So much so that we rarely perceive the transcendent reality our bodies point to. Ishiguro’s characters are especially disadvantaged because they lack the safeguard of the family, they have no choice but to submit to the brutal materialist purpose forced on their bodies, they have been erased from public view, and the reality of their souls has been denied.

But Ishiguro’s characters are drawn from life, so even if not intentionally, the original experiences of creation are written into their bodies and souls shaping their deepest longings and intimating their real purpose. Even in their hazy vision of themselves, Kathy, Tommy, and Ruth sense that they must be made for something more than just use and disposal.

John Paul II calls man's original experience of his body the “threshold” to “his whole subsequent ‘historical’ experience.” We must transcend the murkiness of our own historical circumstances and reach beyond that threshold to fully grasp the meaning of ourselves. In the words of Thomist philosopher, Charles de Koninck:

“We will only be able to understand ourselves when we understand the universe. Our present is filled with the past.”

In the future when I'm able to commit to writing more consistently (i.e. when the baby is sleeping through the night), I’ll consider turning on paid subscriptions. For now, if you’ve enjoyed this piece or any of my other writing, consider supporting my work here:

And as always, sharing, leaving a comment, or subscribing is much appreciated.

You can find the textbook we used here. Highly recommended if you are educating and/or parenting a teenager. Having this knowledge as a teen would have been powerfully clarifying for me.

The original addresses of the Theology of the Body from which I’ve quoted in this essay can be found on the Vatican’s website.

I read Never Let Me Go last year and it’s now my favorite Ishiguro novel.

I love the way you’re reading it alongside the theology of the body here.

I read this book several years ago and the part that always stuck with me was the emphasis on the student's artwork. It's revealed later in the novel that their art was so important because it "proved" the students had souls. Having been exposed to the theology of the body now, I find this aspect of the book much more haunting. Because of their utilitarian purpose and the technology involved in their cloning, there remains the question of what exactly Kathy and her friends are - and if they do have souls what does this say about their dignity and the morality of confining them to such a bleak, inhumane existence?

Thank you for sharing your thoughts! You shed a lot of light on a book I've never been able to quite get out of my mind!