By everything, I do mean everything. The meaning of all human existence is the central question of The Tragedy of King Lear and Shakespeare doesn’t beat around the bush. He gets it right out in the open.

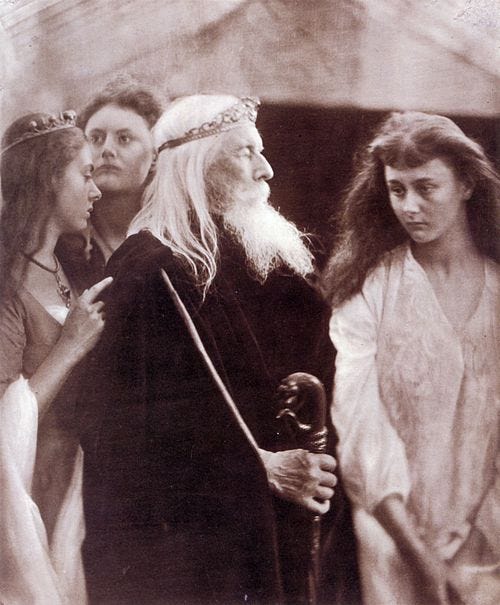

In Act 1 Scene 1, King Lear announces his decision to divide his kingdom among his three daughters: “to shake all cares and business from our age, / Conferring them on younger strengths, / while we unburdened crawl toward death.” But first each daughter must give an account of her love to her father to win her share of the kingdom.

Lear’s elder daughters, Regan and Goneril, immediately spin lies and exaggerate their love beyond reason. The king readily accepts this flattery only to realize too late that “robes and furred gowns hide all.”

Marjorie Garber writes of this scene that it “is one of opulent magnificence and insistent order. It is a scene above all of ‘accommodated man,’ of humanity surrounded with wealth and power, robes and furs, warmth, food, and attendants.”

King Lear is set in Ancient Britain, but every time I read or see this scene, I think, no, this is our world as it is and has ever been. I’m reminded of a story Krista Tippett, host of On Being, often tells of when she was a Cold War journalist and witnessed leaders of countries moving nuclear missiles around maps of Europe. She says, “they were so completely disinterested in humanity.” I’m reminded of corporations, of politics, of the artificiality in the language of professionalism, of platforms and followings, of all the things that signify status and power: in short, of “accommodated man”.

None of it is real. All of it is a game. Only Cordelia, Lear’s youngest daughter, refuses to play. When she is asked what she will say “to draw / A third more opulent than [her] sisters”, she replies, “nothing”. Cordelia takes what Glen Arbery calls, “a metaphysical risk” and breaches this play-acting world. Arbery says: “The subjunctive world of staged relations is imperiled at the outset, and Cordelia lets it fail entirely.”

But if it’s just a game, if this scene in Lear’s royal court is but a plywood stage setting, then what is real? Does this stage’s trap door open to oblivion or to some hidden essence of life?

It depends on what eyes you’re looking with.

Lear’s division of his kingdom obviously concerns the spheres of family and politics, but it also calls the entire cosmos and man himself into question. Just before he lays out his plan to pass on his rule to his children, Lear utters this ominous statement: “Meantime we shall express our darker purpose.” Garber writes, “What is the King’s darker purpose? Nothing less than the division of the kingdom, the willful creation of disorder.” In many ways, Lear’s decision to abdicate his responsibilities as king, father, and man and plunge his kingdom into chaos sets off a creation tale in reverse.

In Genesis, God creates the world by speaking, and it is by speaking that this one is unmade. God sets man a little lower than the angels and crowns him with glory and honor. He gives Adam and Eve his blessing and tells them to “be fruitful and multiply, to have dominion over the earth.” King Lear banishes and curses his child:

For by the sacred radiance of the sun, The mysteries of Hecate and the night, By all the operation of the orbs From whom we do exist and cease to be, Here I disclaim all my paternal care, Propinquity, and property of blood, And as a stranger to my heart and me Hold thee from this forever.

As his elder daughters turn on him, Lear continues to issue forth curses in language that more plainly and intensely inverts the language of Genesis. When Goneril later denies him his entourage of soldiers, he cries:

Hear, Nature, hear, dear goddess, hear! Suspend thy purpose if thou didst intend To make this creature fruitful. Into her womb convey sterility. Dry up in her the organs of increase, And from her derogate body never spring A babe to honor her.

Moreover, the Creation story is one of naming: the naming of all the things that teem in the earth and sky and sea, and, most significantly, the naming of man who receives his identity and nature from his divine father. The trajectory of Lear’s tragedy is the unnaming and denaturing of man.

First, Cordelia is banished and becomes nothing to her father. Lear quickly turns from loving his youngest child best to telling the King of France, her newly betrothed, “we / Have no such daughter, nor shall ever see / That face of hers again.”

Immediately following Cordelia’s departure from the stage, we witness another unnaming. The nobleman Gloucester has two sons, Edgar, his heir, and Edmund, his illegitimate son. Edmund, conceived outside of the bounds of this play-world of status, spins his own lie to usurp his brother’s place; he convinces his father that Edgar is plotting to kill him.

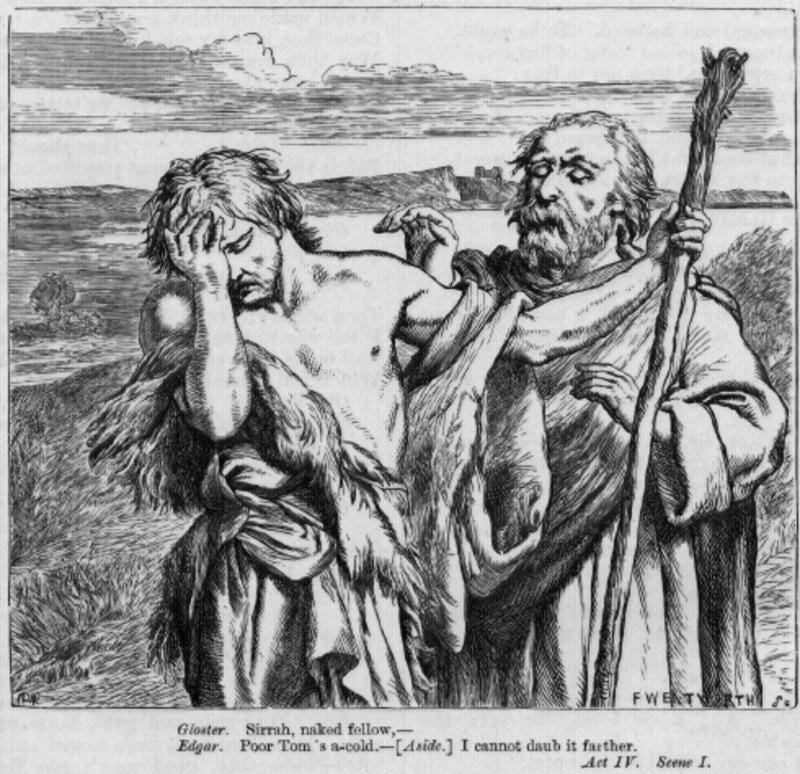

Edgar is then banished from his father’s graces. He flees and assumes the disguise of a beggar, Poor Tom, stating significantly, “I nothing am.” When Lear comes upon Edgar in his abject disguise and feigned madness, he cries out, “Is man no more than this?”

This theme of unnaming and of the question of man’s identity is heightened by the amount of times we hear variations on the questions of who and what throughout the play:

“Who’s there?” (six times by my count) “Are you our daughter?” (1.4.224) “What’s he?” (3.4.133) “What are you there? Your names?” (3.4.135) “What art thou?” (appears three times) “What hast thou been?” (3.4.90)

On and on we encounter these signs of the inability to tell what man is.

But it is the central, tragic figure of Lear and his descent into nothingness that most compels us. In repudiating his roles as father and king, he un-names himself as a person. Once Goneril turns against him, he begins to feel the foundation of his world tremble. He tells Goneril: “I am ashamed / That thou hast power to shake my manhood thus.” Then his panic escalates:

Does any here know me? This is not Lear. Does Lear walk thus, speak thus? Where are his eyes? Either his notion weakens, his discernings Are lethargied—Ha! Waking? ’Tis not so. Who is it that can tell me who I am?

In this scene, too, Lear’s Fool makes several pointed statements about Lear’s identity. He tells Lear, “I am better than thou art now. I / am a Fool. Thou art nothing.” A few lines later, he prophetically says, “So out went the candle, and we were left darkling.”

Lear is subsequently turned out of the staged world of political relations into the tempest. He is driven out of order, albeit of a precarious, man-made sort, into chaos. It is here, lashed by the wind and rain in an impersonal universe, that Lear recognizes too late what Cordelia so clearly saw: “they told me I was everything. / ’Tis a lie, I am not ague-proof.”

Lear will continue to lose his grip on his identity. In losing his mind, he loses the order of language. He loses control over that which sets man apart from beast, the creative power which called forth the universe into being. Indeed, much in the third and fourth acts is a confusion of language. The mad ramblings and riddled language of Poor Tom/Edgar, the Fool, and Lear continue to unravel the “insistent order” of the first act and emphasize the inversion of the creation story.

Lear will reunite briefly with Cordelia, but they will both be taken prisoner. She will be executed. He will die of a broken heart. However, much violence and destruction comes to pass first. Gloucester’s eyes are torn out. Goneril and Regan die particularly horrible deaths. Edmund and Gloucester among others are dead by the end of the play.

Recording the mere events seems to confirm the pessimistic reading the play often receives in which Gloucester’s words are the truest judgment on man’s condition: “As flies to wanton boys are we to th’ gods; / They kill us for their sport.”

It only follows to believe that in The Tragedy of King Lear, Shakespeare offers a vision of “a man a worm” in a world where “all’s cheerless dark and deadly.” It would seem that “we are born to a stage of fools” and through that stage’s trap door into death, we will be met with nothing. And as Lear says: “Nothing will come of nothing.”

But then, it depends on what eyes you view the play with.

I characterized this play as a kind of uncreation myth, but that’s only half of the picture, for Shakespeare sees two planes of reality at once: the immediate and the eternal.

When Lear rashly disowns Cordelia, his advisor and friend, Kent, beseeches him, “See better Lear.” All Lear is capable of seeing in the first act is the immediate realm with its petty political concerns. Yet, as Harold Goddard writes, “From this moment on, the story of King Lear is the story of the slow acquirement of that better vision.” It’s the slow acquirement of an eternal vision.

When Cordelia is asked what she will say to gain her share of the kingdom, she replies, “Nothing.”

The word nothing appears nearly thirty times in this play, and in most instances, it seems to emphasize that nihilistic vision in which life holds no meaning. However, Cordelia’s “nothing” is a richly laden word more akin to God’s speaking the world from nothing into being. Her “nothing” is the catalyst, a kind of spiritual big bang if you will, for the remaking of Lear’s vision and of his world. If Lear destroys the world, then Cordelia creates it anew. “Here, if ever,” writes Goddard, “the child is father of the man.”

It is not only Lear who acquires this better vision. Perhaps the most palpably symbolic (and horrifying) moment of the play is the gouging of Gloucester’s eyes. Gloucester is a foolish man entrenched in his short-sighted vision. He easily falls prey to Edmund’s deception and is manipulated afterwards by his son. However, he does finally risk the comfort of his “accommodated” world to defend Lear, and this act brings his fate upon him.

Yet it is only after he loses his physical eyesight that he can recognize the truth about his life: “I have no way and therefore want no eyes. / I stumbled when I saw.” As Lear is saved by his child, so too will Gloucester be saved by his.

Gloucester, intent upon suicide, is led along by Edgar in disguise who allows him to believe that they are ascending a cliff while merely seeing him over a shallow drop. Edgar then pretends to be a peasant at the bottom of the supposed cliff who witnessed Gloucester’s life miraculously preserved by the gods. That Gloucester believes and is wholly transformed by Edgar’s report may seem a stretch to the imagination but only to an imagination limited to the material plane.

Harold Goddard says of Gloucester’s physical loss and spiritual gain that “there is a mode of seeing as much higher than physical eyesight as physical eyesight is than touch, an insight that bestows power to see ‘things invisible to mortal sight.’” It is here at his lowest point, physically blind and robbed of all pomp and circumstance, that Gloucester may finally do what Edgar commands: to “look up.”

Granted that higher mode of seeing, Gloucester, who has no more part to play in the kingdoms of men, may believe and live by Edgar’s words to him: “Thy life’s a miracle”

When Gloucester does finally recognize Edgar in the last act of a play, he dies of a heart breaking from joy. Edgar reports: “But his flawed heart / Alack too weak the conflict to support / ‘Twixt two extremes of passion, joy and grief, / burst smilingly.”

The references to hearts and their breaking, like the appearances of the word nothing and the amount of times man’s identity is called into question and the references to eyesight and vision, piles up steadily throughout the play. Here’s a sampling:

“My old heart is cracked; it’s cracked.” (Gloucester, 2.1.106) “Wilt break my heart?” (Lear, 3.4.6) “my heart breaks at it.” (Edgar, 4.6.156) “Break, heart, I prithee, break!” (Kent, 5.3.378)

The play opens to a world manipulated by hard-hearted, spiritually-blind characters. When Lear realizes Regan’s falseness in Act 2 he utters the famous lines: “Is there any cause in nature that / make these hard hearts?” It takes Cordelia, whose very name comes from the Latin word for heart, and her “metaphysical risk” to break their hard hearts and to replace their vision of the immediate with that of the eternal.

Nowhere do we behold Lear’s vision so miraculously changed than in the reunion scene between him and Cordelia. It is when he is beaten down by the storm, crowned with weeds, with his eyesight failing and his mind in disorder that Lear sees most purely. When he awakens and sees Cordelia, he mistakes her as one of the blessed in paradise. “Thou art a soul in bliss,” he says.

Harold Goddard writes: “Lear is ‘still, still, far wide!’ as Cordelia expresses it under her breath. Yet in another sense…Lear was never before so near the mark.” Goddard continues to comment on Lear’s transformation: “What a descent from king and warrior to this very foolish fond old man, fourscore and upward, who senses that he is not in his perfect mind! But what an ascent–what a perfect mind in comparison!’”

In this scene where father and child are restored to one another and are led away captive, Lear gives a speech of unparalleled beauty describing what it means to live and to see by grace in this hard-hearted world:

Come, let’s away to prison; We two alone will sing like birds i’ the cage. When thou dost ask me blessing, I’ll kneel down, And ask of thee forgiveness. So we’ll live, And pray, and sing, and tell old tales, and laugh At gilded butterflies, and hear poor rogues Talk of court news, and we’ll talk with them too, Who loses and who wins; who’s in, who’s out; And take upon ‘s the mystery of things, As if we were God’s spies: and we’ll wear out, In a wall’d prison, packs and sects of great ones That ebb and flow by the moon.

Cordelia, Kent, Edgar, the Fool, and finally Gloucester and Lear are all God’s spies blessing one another, seeking forgiveness, singing of eternal things, and wearing out the “packs and sects of great ones”: the Edmunds, Gonerils, and Regans of this world, who only hold power in this immediate realm for a brief moment in time.

When Cordelia’s dead body is brought to Lear and he has given up looking for signs of life, he suddenly says these haunting words before he himself dies: “Do you see this? Look on her, look, her lips, / Look there, look there!”

Composer Franz Liszt wrote: “Art cannot portray heaven itself, only its image in the hearts of those souls, which have turned to the light of heavenly grace. Thus for us the radiance is still shrouded, although it increases with the clarity of understanding.”

Shakespeare has given us such an image of heaven shrouded in Lear’s final lines. These lines are a test of our vision, of our clarity of understanding. How we interpret them says much about how we see the world.

Goddard says:

If, as the old King bends over his child and sees that she still lives, he is deluded and those who know that she is dead are right, then indeed is King Lear, as many believe, the darkest document in the supreme poetry of the world. And perhaps it is. There come moods in which anyone is inclined to take it in that sense. But they are not our best moods.

Our best moods, then, are the ones that open us up to that “power to see ‘things invisible to mortal sight.’” Read in the best mood with the highest mode of seeing, Cordelia is rightly understood as “a soul in bliss” and Lear is truly “every inch a king.”

The world of this play may seem to operate on a far more dramatic scale than that of our own lives, but that same drama plays out in every man’s soul throughout all time. We are all faced with the same ultimate questions as Lear. What is man and his place in this world? Is the telos of the universe disintegration, death, and nothingness, or is there a divine voice, as Lear says of Cordelia’s, “ever-soft, / Gentle and low” that brought creation into being and has sustained it since? In our final moments, will we see a hopeless void or a light that never goes out?

For further reading:

The Tragic Abyss edited by Glenn Arbery Shakespeare after All by Marjorie Garber The Meaning of Shakespeare, Vol. 2 by Harold Goddard

In the future, I’ll consider turning on paid subscriptions. For now, if you’ve enjoyed this piece or any of my other writing and would like to make a one time donation, you can do so here:

And as always, sharing, leaving a comment, or subscribing is much appreciated.

This is just a wonderful article on Lear, thank you! I’ve been studying this play myself and I tend to think (Goddard hinted so much toward the beginning of his essay that you reference) that Lear is a kind of Adam-in-reverse: a fallen king who learns to be a man on his path toward redemption. Lear does the opposite of naming, as you point out, he annihilates identity rather than affirming it, and curses his daughters with infertility. It’s only once he’s broken down into that chaos that’s shameless and without form that he is able to come to terms with his own humanity and need of redemption.

Thank you for the wonderful article, it helped me order some of my jumbled thoughts about the play!

I highly recommend Northrop Frye and Gideon Rappaport’s essays on Lear as well should you look to read further.

Brilliant Dominika! I'm bookmarking this to read again when I next read Lear. I've read it just once and I see I've barely dipped a toe in. *rubs hands in glee* I love when works of art explore blindness and sight. I think it was the Close Reads hosts who opened up my eyes to this in literature and now I see it all the time! (Ha!) Because I'm referencing Gone With the Wind with everything at the moment, I was making lots of connections with Lear and GWTW as I read your essay. They're both tragedies, but I think the same with GWTW as you write so beautifully here with Lear: there is more than meets the eye.